Another Mirage

(Dedicated to Jacques Vallée)

by Swim

Then there was that time we got lost out on the mesa, hiking back from the secret hot springs. We had a map drawn on the back of a Thai takeout menu, with stick figures indicating the abandoned park where we found a rusted swing set and a merry-go-round nearly swallowed by sand. An arrow pointed to a swirl of squiggles signifying an ancient tree that spread its thick branches like a dark cape over the pulverized landscape. In its shade we saw a snake slither off around a perfectly flattened metal can that might have been there a hundred years or only a few days. The gravity was different out in that place, the air thinner. Especially in the pink light of dawn. Things aged and decayed at a fluctuating pace: like my own body, which felt simultaneously asleep and vividly alive, my flesh heavy while my hands fluttered like angel wings.

Once at the springs, we lost the menu (as well as a single earbud and the stack of stapled together printer paper that Lil Mountain–who back then went by the name Jesse James–used for documenting his “ideas about beats.”) Now that we’d gotten there, I figured the way back would be easy enough to figure out, but the landscape rose and fell in unpredictable ways, so that even large landmarks, like the tree, were swallowed up by the hills and boulders. I had only pretended to listen as the woman who told us about the springs (Tizia? Tazia? Tiziana?) went on about how long this and that section of the walk would take. Jesse James and I met her at one of the many thrift stores we frequented, looking for tuff/silly/rare items we could resell. She lurked in its overstuffed aisles, waiting for the proprietor to understand the “special significance” of the badly torn leather bomber jacket she had brought in to sell. It sat slumped on the counter like a carcass while Emerson, Lake and Palmer played on the store sound system.

As soon as I saw her I knew she would speak to me. Despite the heat she wore a sky blue puffy jacket zipped up to her neck and a scarf that was either a designer logo or the Danish flag wrapped around her bowed head. I pretended to look at a collection of Isotopes trucker hats and waited until she was beside me.

“Are you from the City?” she asked.

I nodded, surprised. Not many people referred to NYC in the correct way out here.

“So then you know,” she said, her voice just a sliver of sound, forcing me to move in closer, against my better judgment. “You know what it’s worth. It’s from Brooklyn afterall.”

I nodded again. She stared at me with shiny, heavily lined eyes. Days, maybe weeks worth of make-up had the combined effect of looking almost natural. I didn’t realize it but she’d already given Jesse the map when I went out to smoke, my belly painfully full from the enchiladas and strawberry margaritas we’d gobbled up greedily at the roadside spot next to the darkened Ski Barn.

“Is his name really Jesse James?” she asked later as I handed her a pinch of tobacco. I laughed, mostly at the use of the word really but also at the general situation.

“His porn movie producer parents gave it to him,” I explained. When I thought about his name I thought about how we met, when he was sitting in his Firebird, grinding up weed. Which is odd, you know, because he never smoked.

“I just trap and pop pills,” he said, right from the start, and I realized the weed was for me. It was weird and kinda sketchy but I didn’t ask and I didn’t care. I had to leave Odious and HeirMax98 and he had a car and said he’d take me all the way, all the way out west.

His name is a part of me, just like his stories. A fabrication imbued with truth. Or truth imbued with fabrication. Like how his father explained to him that all movies were the same, it was just that the movies he and his mother worked on zoomed in a little more on certain details that made some people upset.

“But it’s all empty,” his father said, “none of it means anything it just seems like it does.”

He grew up with his parents in Portland, Oregon in a second-floor apartment of a large Queen Anne style house from the 1890’s that was on a special list of historical sites, the exteriors of which couldn’t be changed without the agreement of the rest of the neighborhood and the city. When Jesse told other kids where he lived he never specified that they only lived in one apartment in the gigantic house. He learned early on that what you choose to leave out when you tell someone something was often more important than what you included. Regardless of how it was divided inside, the entire house was his domain. Its majestic frame and looming façade merged with his psyche. Years later, after he ran away, he had a recurring dream of trying to get back inside through a long parking lot or a forest, but the house kept receding into the distance, a dark shadow on the horizon. One day (the guess is maybe it was an earthquake, a highly localized tremor) the tall brick chimney tumbled off the top like dead winter leaves. It had been the defining characteristic of the place--the thing everyone always commented on when they saw the house for the first time, or how they referred to it to others (“…that big blue Victorian with the crazy tall chimney”). It remained as a pile of bricks in the yard for several years, a project on the imminent horizon, until the landlord finally admitted that they weren’t going to be able to rebuild it. The way that grass blades grew up around the faded rose colored bricks, the edges of which were cracked and crumbling and turning to dust, made Jesse imagine how one day the whole street—the whole country!—would be nothing but ruins. Looking at the bricks made him feel the certainty of a rapidly approaching end. It gave him a strange sense of standing in the future and the present at the same time.

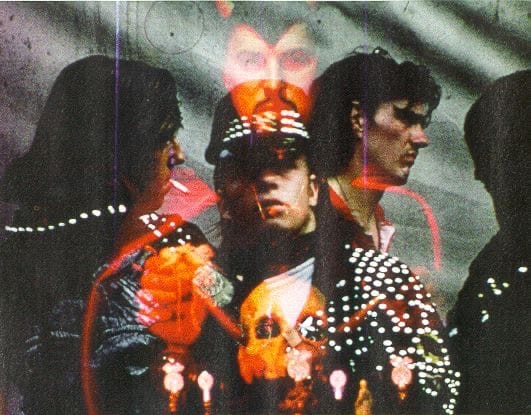

The rumor was that his parents met on the set, and that his mom was an actress and his dad a director. The reality is that they started as techs (his dad was a gaffer, what his mother did I don’t remember) and then worked for producers, their jobs being to figure out who else should be producers based on whether they had a lot of money or knew people who had a lot of money. He liked the rumor better. It helped that they were both so good looking. His mother had the naturally white blonde hair of very young children, while his father looked like a Rockstar, his brown hair long and feathered with a subtle orange tone, like a lion’s mane. Everyone thought it was fake, and asked him who did his color. He had thick mutton chops that he wore even though they’d been long out of style.

“When you find a look that works for you, keep it, no matter how things change,” he explained to Jesse.

But despite this advice, his son changed all the time. So much so that it’s only been a few months and his face is already a blur.

Jesse James in the thrift store parking lot, sucking on a soda pop:

“C’mon, Swim. Let’s go. Don’t you want to?”

When the lady said (with a wink) that to get to the springs we’d cut across private land, I assumed there’d be fences and houses but after parking the car in the black predawn and walking for an hour or two along a deserted, mud-covered road with potholes the size of whole cars where pieces of dried, torn tire and a hubcap were strewn, we stepped over a chain from which a “No trespassing” sign hung and climbed over a half submerged drainage pipe and ahead of us was only sage bush and and the looming shadow of the gorge in the distance. I felt in my pocket for the takeout menu. Where were the people? Where are the houses? The air was cold as we hiked down to the bottom of the gorge where I touched the Rio Grande for the first time. Up close it was like any other rushing water, the stories it seemed to contain when looked on from up above dissolved into the landscape around it. The springs themselves were natural pits beside the river that were covered inside with a carpet of soft algae. We stripped off our clothes and slid inside, waiting for a blast of heat that never came. The water was pleasant, like a tepid bath. I lifted my face into the gentle rays of sun beaming down from the top of the gorge, mimicking the motions of those who came before. Dusty stagecoach passengers, traders, Aztecs.

“Just think”, I said, “These springs have been bubbling down here for many hundreds of thousands, maybe millions of years. The long ago result of the earth’s plates moving, of the planet groaning and growing.”

“Maybe we’ve been here before,” Jesse said. “Maybe one of us killed the other.”

“Maybe one of us gave birth to the other.”

“You could have been an Aztec warlord and I was your slave.”

“I might have been a bug and you stepped on me with your cowboy boot.”

“Or we were both those guys, flying high,” he said, pointing up at the black vultures circling above.

“Yes, that was us,” I said, “for sure.”

*

Sometimes, even now, when things are going all crazy and terrible events have happened that can’t be undone, no matter how much I wish for them to be, I think about the springs and how they are doing their thing no matter what and whatever it is way up here will just happen and be over with while they keep bubbling and boiling and river keeps rushing.

There was no one but us down there. The springs truly were secret, or maybe just illegal. The woman at the thrift store said they used to be open to the public, but there was too much littering and partying and issues with the people who lived nearby, so a few months ago, after vigilante type actions raised the level of concern, they closed the road. But it was still possible to get there if you were willing to walk to the edge. The town no longer takes care of the narrow trail that led down the gorge. We had to step around cascades of scattered stones and ease ourselves carefully over slippery sand. In a few years it will be covered completely.

On our way back we walked with heavy steps through the sage bush so any snakes would know we were coming. But they were probably deep in their holes as the sun reached the middle of the sky. There were bloody stains on the parched earth where the coyotes had killed something a few hours earlier. They too, must be sleeping–it was only us and the sage and the faint rush of invisible silver jets way up above.

It took us a while to realize we were going in circles.

“Where’s the tree? Why can’t we see it when it’s so big?”

“Maybe it got chopped down,” I said, annoyed by how busted we were, how we didn’t even have enough water or proper shoes. I’d say it was because we were city people and far away from home where we knew how things worked but I knew I was useless there as well.

Jesse James laughed.

He was good at that, laughing when things weren’t funny.

“With or without the tree, we have to find something that looks familiar,” I said.

“All I’ve got is you, baby,” he said, offering me a smoke which I declined because they made my throat more dry.

We tried to find a trail, and when we couldn’t, we pretended that we did and started walking. I forgot about stepping heavily, it was enough to move at all, knowing deep down that it was likely in the wrong direction.

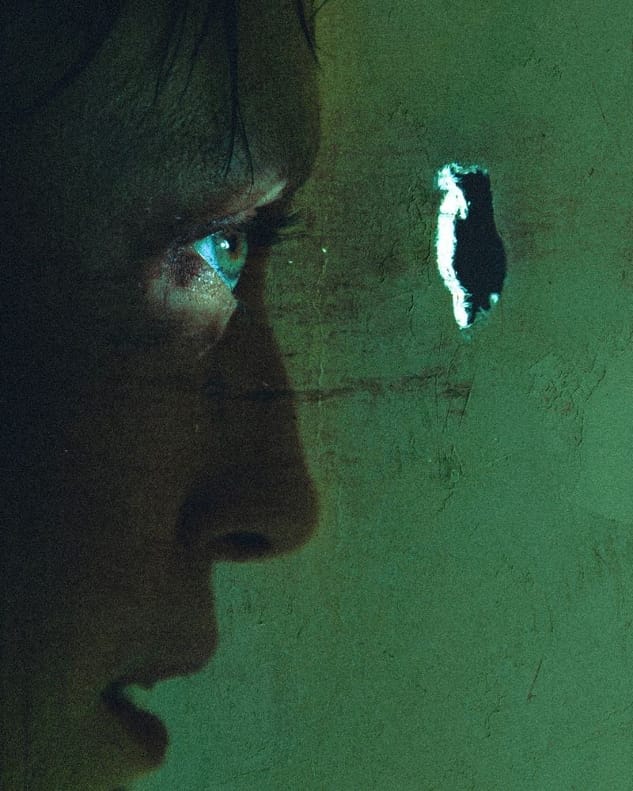

It was another hour, maybe two, before we found the first boulder. At first I thought it was a trick of the sun, but as I got closer I could see that it was painted white.

“It must be a property marker,” I said.

“Maybe,” he said, toeing it with one Air Force and then the other.

“But there’s nothing here. No driveway even.”

“It’s probably here, but we can’t see it,” I said, having convinced myself that there were secret dwellings all around us.

We kept walking, heading in the direction of a silver mirage on the horizon that we hoped was the highway.

Suddenly, in the middle of the bush, there was another boulder painted bright white. Among the washed out green, gray and beige it seemed to glow with a strange insistence.

My heart pounded in my chest–not with trepidation–but with a sudden influx of joy and another emotion I couldn’t immediately place, but would turn out to be relief.

“It means something!” I said.

“No it doesn’t,” he said.

“What’s it doing out here then?”

“Nothing. It’s just here.”

“We didn’t see it on our approach, it just happened to be right in front of the way we were walking, just like the one before.”

“Maybe we didn’t come this way.”

“We did,” I said.

“Really?”

“Absolutely, of course we did,” I said, as though by sounding convincing I would make it true.

“Well, anyways, so what?” he said.

“So, I think we should move it.”

“What? Why?”

“I think if we do we’ll find the way out of here,” I said, an idea that occurred to me as I said it.

“I thought you said we were going the right way.”

“We are, I mean, generally. But maybe not specifically. Not exactly.”

He took off his sunglasses and stared at me from the swollen slits that surrounded his eyes. I wondered if he could see out of them at all.

“Why do you think moving this rock will do anything?”

“Because it will change things,” I said, as the excitement in my gut changed into anxiety and then back into excitement. “We need to change something.”

“No, c’mon, just leave it alone and let’s keep walking.”

He started walking but I stayed put.

“It will just take a second,” I crouched against the boulder and pushed as hard as I could. It was heavier than I thought, or perhaps I was weaker. Jesse James/Lil Mountain just watched as I struggled before finally rolling it over.

“Look,” I said, “The bottom is gray! So it was definitely painted.”

This was back when I was convinced that he was going to die in a car crash on a lonely highway. And now that I was riding with him, I would too. He had a dangerously symbiotic relationship with the Firebird. It had a third eye and told him things, the information bleeding through the steering wheel and into his skin. It welled up as pop music, the fiery crash and death felt inevitable. For all those miles I could feel it: something was going to happen.

But now I know it wasn’t a crash, but the approach of a different kind of impact. Like an explosion, when all the air is displaced with a giant POP. Only not the real life experience of it but a video played on repeat, without sound, turning something deadly into something beautiful, like a flower blooming on time lapse.

Soon after I moved the boulder we spotted the silver swirl of the highway out in the distance, wondering at first if it was another mirage, but it wasn’t. It was real, and we made it out–or at least that’s what I thought at the time.

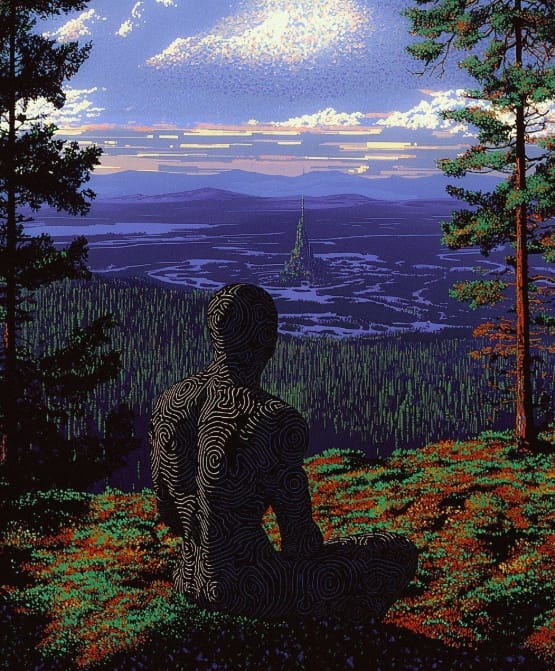

Image: Grażyna Smalej

Thank you to everyone who reads this and to all who subscribe. Paid subscibers get Odious's posts + mine sent directly to your inbox.

All $ goes to mutual aid.

Or sign up for just my posts for free. I'm considering locking down to subscriber only but who knows. Anyways, it's nice to have things sent to you from a friend.

Much Love in the Dub.

--Swim