hateful waves

by Swim

Cyndi kept checking the time on her neon green Swatch watch. It didn’t have numbers or a dial so she had to squint, which caused the lines around her eyes to stretch out. She became not just old but ancient, like a wood carving of a hunched deity or local spirit. She floated far above me, all knowing and justified in her belligerence.

The watch was translucent, its interconnected spokes and springs and other guts on display. Several of The Babies sported the same model, either in green or a lurid pink. Cyndi claimed that sharing was her crew’s “A-number-one” value, but I realized (too late) that by spreading out a haul what she really did was turn The Babies into accomplices. She made it hard for them to leave.

She didn’t offer me a watch or anything else, as I was her student, or so I made her believe.

“The time is out of joint,” I declared, after she looked for like the tenth time. I was tripping a little harder, and wishing I had my phone so I could see if it had been a few minutes or hours. The other way to find out would be to ask, which I wasn’t going to do. The rest of the house had wifi that shut off late at night, but Cyndi’s room was always free from the “hateful waves” as she called them. She said they caused cancer, depression and infertility. I never picked up a single bar in the whole fake town, so my phone was as good as dead in her room, but Cyndi still made me put it in a little basket by the door.

“Otherwise you’ll be trying,” she said, “I know you will. All y’all are addicted so bad you’re always trying, just to get on for a second, just for a quick hit.”

“I’m tryin, I’m tryin, I’m tryin,” I sang.

I was lying on her bed with my Wayfarers on, despite the fact that it was dark out and I was inside. Even though my eyes were hidden by the glasses I was still careful not to look over at her and to remain evenly spread out across the bed, so she won’t try to squeeze in next to me. She wore a gauzy black, off-the-shoulder top and ripped designer jeans that showed lots of skin in places like her upper and inner thighs.

During those last days I generally felt alert and awake, even after being up for days, and yet when I went to do real things, like riding a bike across a field or climbing up a pile of stones my body was less and less cooperative, as though it was receding from me or I from it. It wasn’t an illness, but a loss of signal, something to do with the nervous system. The dead zone was killing me, bit by bit. Back at the start I made the decision to keep Cyndi close instead of trying to leave and risk her retaliation. But even by the end I didn’t understand the plan. Were we recruits for her stalled and disintegrating revolution of crust punk merry men? Or just new blood to keep the existing (and horny) troops entertained? I had to figure out what she wanted from us and if necessary try to dissuade her from it. But instead I did what I do best and retreated between the walls and into my thoughts as the unknown person moaned in loneliness and anger somewhere far beneath me and the last act rapidly approached.

The old me would have been pissed off and annoyed, but I just felt bad. They were trying so hard to say something, and failing over and over.

“I’m trying, I’m trying, I’m trying, I’m trying, I’m tired!” I shout-sang up at the ceiling. The words were filled with the drunken emphasis of real feelings–it was true that I was trying, even if it seemed like I was doing nothing. There wasn’t a single morning that went by that I didn’t recommit to my vow to figure out a way to love and help others.

Cyndi ignored me and checked the time again. She felt it too, this thing that was coming. Maybe it was lodged in her body, like it was in mine. She grimaced when she got up and sat down. Not since the Lyme had her joints been so swollen, the skin pulled tight and shiny over them.

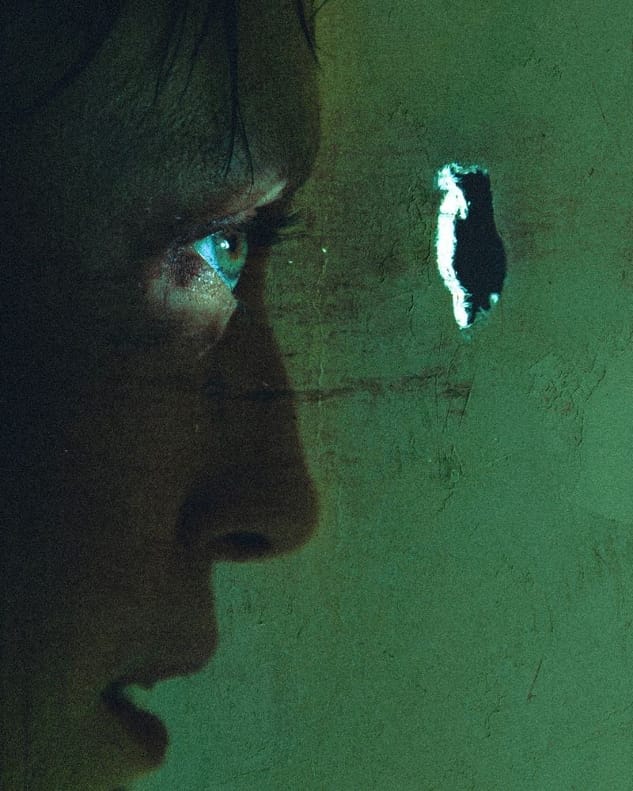

I want to tell you about the crash, about everything I remember and don’t remember but have pieced together from other sources. This method is necessary given my intoxicated state at the time, as well as the fact that a certain surrealism has become the foundation for my experience of reality. I can see now how aspects of the crash happened before the physical event, echoing backwards in time. For instance, the way Cyndi kept putting a hand over the same eye that would be injured, while she giggled and sipped more of the cocktails she’d made out of ground mushrooms, lemon juice and whiskey.

“Why are you wearing that stupid human suit?” she cackled. I laughed, surprised that she was quoting one-eyed Frank from “Donnie Darko”, but I’ve come to wonder if she really was or this was just something that occurred to her to say.

“If I can’t see you, I can’t hear you,” she snorted, making herself crack up as usual.

“Shhhh.” My magic shuffle was playing on the cheesy yet beautiful glowing LED bluetooth speaker and I wanted her to hear it. I wanted her to experience this gift of sight and sound.

“Every song that comes on is a secret message,” I explained while she ran her claws through her golden seaweed hair. A religious program played on mute on the TV as “Manta Ray” came on, a Doolittle B side I hadn’t heard in years.

“‘He has no memory of flyers in the night’,” I sang, my voice radiating with a real and actual joy.

“Jesus, Swim. What is this shit?”

“The Pixies.”

“Good Lord, do we agree on any music?”

“I don’t know. Iggy Pop?”

“Yes, maybe. Ok.”

“But you should like The Pixies. They’re down with foul witchy stuff. ‘Is she weird, is she white? Is she promised to the night?’” I couldn’t stop singing, whether it was a song on the speaker or just in my mind. It felt so good, like surrendering to the present moment for real and not just in theory.

I’d forgotten about singing and I’d forgotten about dancing. I’m not sure how or why but it was coming back.

“Fucking hell that’s corny,” she said, and cackled again, the sound like the yelping of the coyotes we sometimes heard at sunset.

I was on the bed because I was slayed by the roast Cyndi made for me, the first meat I’d had in some time. I had a large glass and a bottle of white wine near me on the floor by the bed, the idea being that it would slow me down on the cocktails.

“I feel shockingly full,” I said, giggling as I reached over to pour some more wine in the glass.

“You’re not used to real food. You’ve been living off of protein bars and green tea.”

“Melted protein bars,” I said. “I can only get them down if they’re soft.”

“No one can go on that way, let alone a leader. The leader of a movement.”

She was right, I’d been having a hard time swallowing food that wasn’t packaged. This isn’t the first time this happened, when I needed food to resemble as little as possible something that had been alive. Pizza bites and Dove Bars. Cap'n Crunch without milk. Cans of Japanese soda, with their cosmic colors. The texture of real food, especially meat, was too much for me.

“Yeah, well it’s a thing. You saw me. The meat made me gag.”

“But only at first, once you had a few bites you couldn’t resist.”

“It tasted good,” I said, not sure if this was true.

Cyndi closed her eyes and leaned back, her cane planted firmly in front of her.

“The pink and juicy meat, covered in brown gravy. The spicy boiled potatoes—the bright orange carrots. Warm nut bread…sea salt and sweet butter…Italian mineral water…all of that was great but you know what the most important ingredient was, the one that made you able to eat it?”

“I don’t know,” I said. I sometimes wondered if Cyndi put poison in my food, as well as that of The Babies.

“It’s that I made it with love!” she said, tapping on the floor.

“If you make something with love it becomes a magical nectar. It will nourish and heal you no matter what it is!” Her voice was high pitched and very loud, almost excruciatingly so.

“Even a Domino's Pizza?”

“If someone makes it with love, then yes.”

“I don’t know,” I said again, as I fought off waves of nausea. I was pretty sure that whatever love Cyndi thought was in the meal was counteracted by the fact that a large part of it was dead flesh. Odious once explained that animals on farms died with hormones of fear flooding their organs, and when we ingested that it made us sick on body and mind. I believed them but didn’t change the way I lived, wearing my leather shoes and ordering my deli sandwiches. But when I was out in the woods I became unnerved by how cats and dogs and squirrels and baby black bears looked back at me. We held the gaze of the other and caught little glimpses of things inside, a flurry of feelings that were exactly the same.

I don’t want to be a vampire. Wasn’t it Gandhi who went on about how we transform ourselves into something cold and disgusting when we hurt others? I want to be warm. I want to radiate light. I don’t like taking from others. But I’m so used to it, I don’t know what it would mean to stop.

While at Cyndi’s I often thought about leaving. The only problem is I didn’t know where to go. I spent my days locked in the room with the moaning forcing me to go over it again and again–did I take The Babies with me to the City, where we would find Em and then Odious and figure everything out, or should we blow the whole scene, and go back out west, where the sun and the sea would fill us with much needed vitamins. We’d nip it just in time, Odious would recede further into the realm of myth, and everything would be OK.

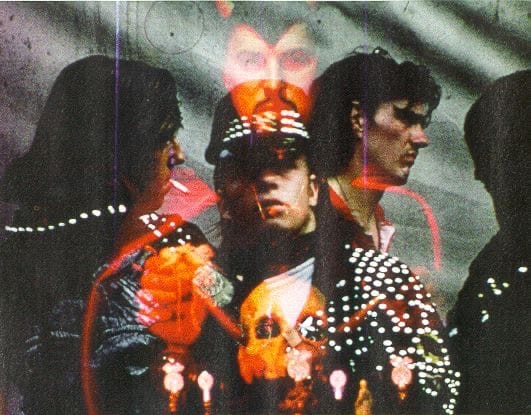

These were my thoughts during the day, as I started planning where we would go and what stops we’d make along the way, saving bookstores and scenic lookouts on Google Maps, but when it became night someone came by and unlocked my door and the performance changed. I drifted downstairs and took my mind off all its questioning and just observed Cyndi’s whole sick crew. They were filthy–the room smelled like dirty boots though they would say it was the smell of real humans. With all my perfume chemicals I’d forgotten what it was like. Their jeans were baked on, their arms tan and fingernails black. They were against detergents, mass produced oils and flouride in any form and after a long day’s work preferred to bathe in the river while shotgunning tallboys. I thought I saw, but couldn’t be sure, a few of The Babies mixed in with them. They lay together in big sweaty masses, bloated like seals, losing all individual form and differentiation except for their eyes, which glittered in the shadows with mischievous intent. They were high, “post-zenith” as they called it–constantly involved in activism and art making, even if it was very subtle forms. They misplaced lighters and lost baggies in the couch cushions. It could be anything that was going on, but it was always something that was simultaneously new, brutal and deeply ordinary. There was a never ending work flow, of tasks to be taken care of–orders, both direct and indirect, that came from Cyndi. They asked me to help and I always said no, my job was to watch. I said it with a certain authority that made them nod their heads. I sniffed as they rolled backwoods blunts and worked with inspired diligence on jewelry made out of bullet casings, SSCI ports, and Nike Keychains. They stretched canvases and filled them with neo-DaDa collages of everyday objects and visuals. Pix of lines of coke, orgies, broken machines both real and imagined…they saw no issue with bringing nightmares to life–we were alike in that way. I crouched beside them while they used garbage and things from around the house, bits from the movies that played constantly in the background, always on mute. Teeth that were knocked out got saved, x-rays of broken bones were adorned with poetry. They passed out codeine and kratom which dragged everything out into one long process of passing out. I woke up looking up at a green lantern hanging from a rafter while a girl wearing a Police T-shirt, pink panties and an ancient walkmen walked in circles kicking the floor and screaming, her eyes glazed and her lips swollen.

“This is a lot of effort,” I remarked, as we put on paper mache animal masks and walked out into the woods.

“You could just copy and use the text and ideas of others,” I said, “It’s not like anyone will know, and even if they do,” but unlike me they weren’t worried about running dry.

We sat in our masks under half living skeleton trees that were hundreds of years old and the wind whistled as someone who was very tall and wearing all black with a metal mask of an abstract, frowning human face suddenly brandished a torch and lit on fire the canvases they had been working on with such diligence. As they crumbled to pieces and turned to ash I felt that rare tinge I get when someone hits or nearly hits the goal, which in this and all cases, was a performance indicating the empty placeholder at the heart of the matter.

“Werd”, I said, and admiringly hit a sickeningly sweet vape that was handed to me, the white plume twisted up with the grey smoke. It was hard to move my head but I looked back to see the source of the subtle yet still bright lighting which is when I saw the bloom of carefully positioned cameras.

“Of course,” I muttered to The Babies sitting next to me. “At the end of the day it’s all about the stream. The propaganda. The viral weapon.”

Back in her room, Cyndi got up and changed the channel. To do this she had to turn a dial–the picture jerked then flashed off and a new picture jerked into place. It was a very specific type of violence. Each time it happened my heart jumped as I waited for the static to appear, but it never did.

There was a Roger Altman flick called, “The Long Goodbye” that was about to start. At first Cyndi went on about how the casting was all fucked up, how Humphrey Bogart would always be the real Philip Marlowe, but then she got quiet and we just watched. The sound was on and coming through the little speakers built inside of the TV. There were no subtitles but it turned out the sound was better than I thought and without the words on the screen it was just the picture which was nice. The opening scene was about how the detective Philip Marlowe (played, in a laid back way by Elliot Gould) wakes up late at night with his cat meowing like crazy because it wants to be fed. He lives in Malibu, in a busted apartment that doesn’t have a proper lock and key opening but a padlock. It’s more like a clubhouse than a real home. He smokes one cigarette after another as he makes the cat a bowl of sourcream and raw egg that he pours some salt on and mixes with his finger but his cat just sniffs its nose at it, wanting only to eat “Courry brand cat food” so Marlowe has to go to the store, which he does, passing the crew of half naked hot stoner girls who are his neighbors. One of them asks him to pick up some brownie mix for her and he obliges, because, as we can tell, he’s a cool man, living outside of time and place in his suit, smoking his head off and bounding around in a way that was enjoyable to watch. So much so that I didn’t want it to end, this little late night story to watch as a respite from my own, which continues with him at the 24 hour supermarket where they’re all out of Courry brand cat food and he’s forced to buy something else, which he brings home to his now-frantic cat who he attempts to fool by keeping it locked out of the kitchen while he pours the new cat food into an empty Courry Brand he takes out of the bin. Then he lets the cat in and pretends to open the old can. He puts the contents into the bowl, exclaiming about how great it is but the cat sniffs its nose at it once again. Then, much to Marlowe’s chagrin, it takes off outside via a small cardboard cutout in the window labeled “puerta para gato” in black marker.

It’s when Marlow’s looking for his fussy pet that his human friend Terry pulls up, cool and rich and whatever but also in trouble. He asks Marlowe to drive him to Mexico, and because they’re homies Marlowe does it without asking for any more info and this is the beginning of the actual story which is when Cyndi started talking again and we stopped paying attention. Still, it was the longest I can remember being quiet in a while and certainly the longest I’ve ever been quiet around Cyndi.

Watching an old movie on an old TV in an old room felt good. I stopped worrying about the time. There was a memory of a feeling but not actual thoughts. It was night but I wanted there to be birds singing outside. If we stayed up long enough it would happen: there would be a bird, like there was the other night here in the city, a single bird at 5 AM when it was still dark but I could tell the light was coming. The bird sang a song so beautiful, filled with the same fear and sadness and hope that fluttered in my stomach and in the back of my throat. Was this a nightingale? I don’t know, but in the film in my mind of those last moments before the crash I edit in the bird song that I heard after it, here in NYC, where I’m waiting for Truth Itself to emerge from out of tiny hard fists and cold grey buildings covered with scaffolding.

“I’m waiting, I’m waiting, I’m waiting, I WAIT. Deep inside, deep inside these hateful waves.”

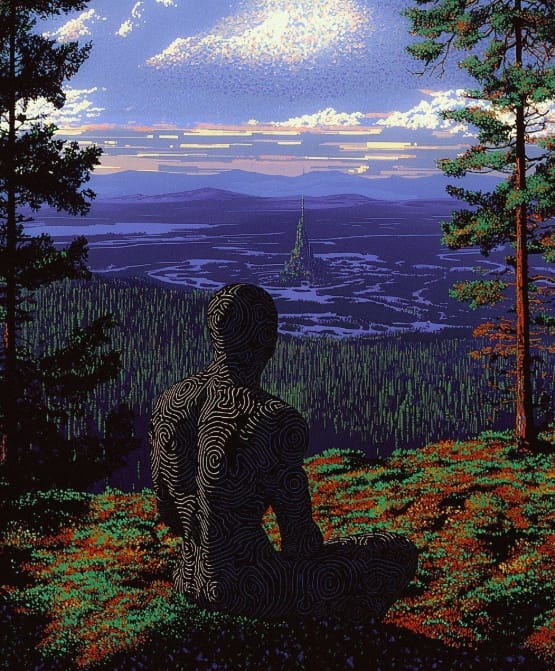

Image: Katie Morris

*Get my posts AND Odious's

All $ goes to mutual aid projects.

*Or you can subscribe to just receive my posts (like this one) which will be sent to your inbox for free.

Love,

--Swim