Invisible Helpers

by Swim

“So let’s figure it out,” Cyndi said, brandishing a wooden cane painted bone white above her head. “Who the actors are and who is with us in real life.”

The cane was from several years ago when she had Lyme Disease and nearly died. It had gone undiagnosed for so long that it ate away at her brain and nervous system, so that she couldn’t talk or walk right.

Now, with the exception of a faint limp, she was able to walk fine, but kept the cane along with other reminders of how she’d beaten a death that would have never come so close had she only listened to herself instead of other people.

I resisted the urge to duck as she swung it over my head, cackling as she did. I’ve come to learn that Cyndi is indeed strong, and if she wants to hit me she will, regardless of what I do.

After what happened and how hard it was to get the blood out of the crack in the rental’s windshield without breaking it even more, she decided it would be best if I got a little space from The Babies. She said our stories didn’t add up. Thus the statement about figuring out who is real. Hearing her say this sparked something inside of me, as I too have lingering doubts about who is on my side and who isn’t. I leaned my head on her shoulder and closed my eyes while she took a selfie, the cane glistening between us.

We spend time together. She’s making a show of how she’s taking care of me. She drives me to her favorite bagel place where I get an orange juice. She takes me to Walmart and we walk the aisles. She bought me a stack of v-neck t-shirts in various colors and made out of a mysterious stretchy, synthetic material, a pack of white hiking socks wrapped in plastic (the dark colored ones I had wouldn’t reveal the presence of tiny ticks) and a brown bottle of liquid codeine.

“For that nasty cough of yours,” she said.

I get the feeling she sees me as a student of sorts, someone to whom she can impart her vast knowledge about running a cult.

“At the end of the day it doesn’t matter what you do. As long as you’re not under any illusions. My advice to you would be to do an internet fast, and treat this time as a vacation. To figure out what’s what. Because based on some of the shit I’ve been hearing about I think you let your ordinary reality overcook like a turkey in the oven, so that now it’s burnt but still ordinary until you keep thinking about it and suddenly it flies out of the oven and out of the room and into space.”

Cyndi doesn’t realize there’s a mole. Several, in fact. Despite her attempts to keep us separated, Cyndi’s kids take my paper missives and deliver them to The Babies. The irony isn’t lost on me that it’s only now, with everything completely broken down and firewalls both real and imaginary blazing around us and the police bound to barge through (or attempt to barge through, as it is ingeniously fortified) the front door at any second, resulting in a gun battle with Cyndi’s family that played out in my mind with the same frenetic and desperate staging as action scenes in Bonnie and Clyde, that I have become the fully actualized leader of these children. For so long I was holding on, trying to understand and trying to exert control (same thing) but now, with what seems almost to be a natural occurrence, I’ve fallen in sync with their (anti)communication methods. We can’t send texts so we send text art. Bricolage made to Timbaland beats on the CD player mashed with raw nostalgia. They send the sketches for how they plan on dressing their avatars for the latest RPG psyops they found via hidden links on fake listicles. By the time they’ve answered all the questions to gain access to the game, it’s already over, but the fits live forever. My responses–whether coded in the form of a to-do note or a poem written to the greatest thinker of our time–are strong and sappy like the wood of the pine tree we cut down, back when we were all together. I used it to craft a frame around the memory of the mountain, a space container full of holes that let me look deep inside. I’m finally catching up–Trainspotting the skibildi toilet, diving deep down with bits of light infused tp sparkling like stars around my shaved head while The Babies spend their time getting younger. They have combined living outside with living inside, in a world of their own collective mind. They hack the Speak n Spell in the forest sward, singing through the wires, complimenting and conspiring with fairies in the feedback, phoning home to Jesse James on hijacked frequencies. They keep hitting all the best letters, b as in boy, v as in void, but all they hear back is noise.

“I think it’s Ok that you let them think he’s still alive,” Cyndi said, while she cooked me up a plate of meat. “It gives them something to do. But then again even you didn’t see a body. All you’ve got is that rolled up piece of paper.”

“All I’ve got is Odious,” I said.

Cyndi rolled her eyes.

“I can’t believe you’re just letting this thing go on and on. Look at me, rearranging and resetting this little revolution of mine just enough to keep it going but not really trying to make it anything more than it is. I got this far and that’s good enough. But you? You could do something else. Or can you? You know what, now that I’m really looking at you, maybe you ARE old. I mean, you look like shit so it’s hard to tell but maybe you’re like, really old already. Like me.”

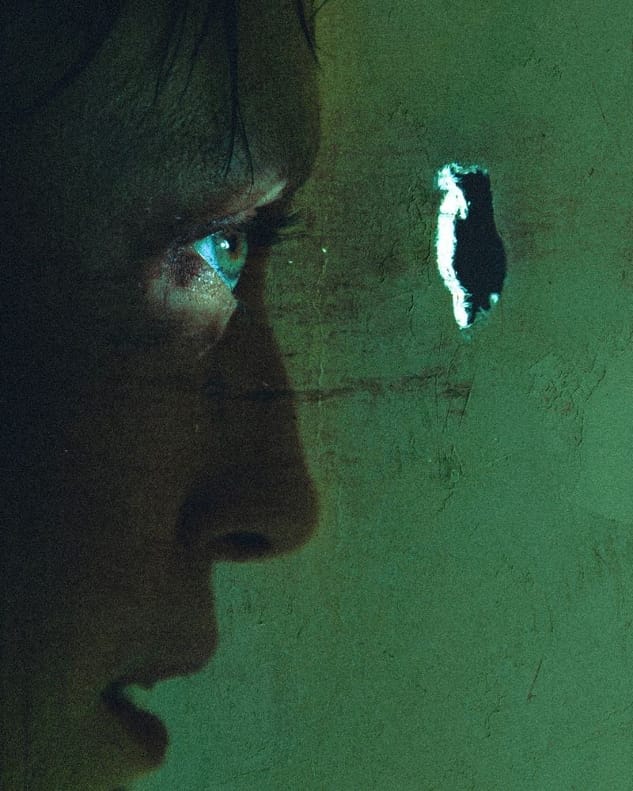

Alone in my room I’m always listening. I know what’s close and faraway. There’s the clicking of hardened mucus inside my sinus cavities and the gurgle of the Walmart mini-humidifier and the relentless dripping of thick water from the sink. From where I’m perched on the futon I can see the water glistening on the spot where the white porcelain has been worn away by the constant dripping to reveal a bright bird egg blue underneath. Further out things come in reliable patterns, the sound of plastic sucking in and out as Cyndi walks by in her puke green crocs, (they aren’t really puke green, only when I hear the sound and can’t see them) shouting at one of her kids or into her satellite phone, followed by the snorts and scratching sounds made by overgrown, splintered black toenails scaping century old orange wood as Babylove, the Pitt makes her furious rounds up and down the hallway. There are microwave beeps, phone chirps, the sound of metal sliding against metal or clanging on the floor. But then, all at once, the doors slam, several times in quick succession, and in the sudden silence I wait for it to start. It’s coming from somewhere beneath me–low moans, at first I thought it was an animal–but I can tell now that it’s a person. There are no words, just the sounds of someone bellowing in pain, the kind that’s not an immediate emergency but is nevertheless unrelenting. Someone post-verbal who is crying out from the deep ache of suffering. It only happens when everyone else is gone, which I understand to mean that whomever was watching over them has left as well. I can only make my text art missives when the house is empty, and there isn’t the threat of someone barging in at any second, so I try to work through it, but of course the sound gets sucked into the text, its sadness imputes itself on the words I choose. At first I tried to stop it and filter it out, getting precious about what was mine and what I was making, but then, in my more self-aggrandizing moments I congratulated myself for helping them communicate. This unknown person, stuck like me. I pace my little room, forgetting and then remembering that The Babies said I was almost certainly being filmed, at which point I become aware of my face, and how my expression is an ugly mix of concern and annoyance. The person goes on and on, demanding assistance. I think of finding the way downstairs to check on them but I never do. The rule is I’m supposed to either stay in the room with its toilet covered by a plastic curtain and drawings of western vistas on the wall or take the stairs out the side entrance. The rest of the place is off limits. But the real reason is because I’m afraid. The voice is sad but there's anger in it too. I feel like I will go downstairs and find something I’m not ready to deal with. I either imagine or was told and can’t fully remember–hence the thorny nature of this particular fear–that the perimeter of the house is larger than it seems because of all the secret rooms and underground tunnels beneath it, which in turn connect to the unfinished pipe system left to rot by the town and taken over by the bears, who are undoubtedly happy to let freedom fighters with hearts of gold like Cyndi and her family use them without a hitch. I picture Cyndi’s family under there with headlamps and snicker bars, dried fruit treats and jeans too tight as they plot and train to defend this unchartered piece of land with its dead soil and bogs and quicksand from the government troops who might invade at any moment.

Meanwhile The Babies are waiting for my next message. “Next” is a funny word because I work on several at once.

“The Fear that all Houses have Mazes Beneath Them is Something with Which I Struggle”, I write in cursive and then cross out. Not in a way that makes it still possible to read but all the way, so it’s just a series of dark marks.

Text art is a very practical mode of aesthetical expression, because I can squeeze everything on one page, all the words I don’t understand, leaving out the definitions I either have or have not looked up on my phone and instead drawing lines to connect the ones I think go together, long lines in different color Japanese pens, trajectories that trace the arcs of certain days, of successions of days, whole years marked in dashes. I return to the page again and again, writing down quotes, plots to movies, bad dreams, real dreams (i.e., visions) like the one I had two years ago of a future Buddha while I was doubled over with cramps and staring into the toilet, such an unlikely place for an advanced being but that’s the point–for a truly advanced being all places and things and people are the same. But what about feelings? The feelings we have of others? Are those all one and the same? Specifically, the feelings others have about me? I use a Polaroid of Em to mark the place in my Brett Easton Ellis book, reading him always gets me amped. A Buddha as a Bookmark. A Buddha as a Spy Who is Right Now Pitching Her Book About All My Secrets. Taken as a whole, The Babies are not Buddhas. They are 19, 12, 16 years old…literary ages and getting younger still. They have iconic, tan bodies that make me feel great because they make me feel nothing. I think of other old cranks who hung out with children, like Larry Clarke. I saw Kids in the city when it came out when I was a kid and it was also nothing. And in that way it was life changing. I couldn’t believe that it was a movie about everyone I knew, some of whom were sitting next to me, wasted and wasting time in the A/C like the kids on the screen. It was so jarring that I walked through the projected images to the other side and became someone different. I slipped through the screen and the scene. I went to an artsy school and read everything, but not before fixing my broken brain so I could concentrate. I went from two seconds, to five seconds, to 30, and then five minutes and finally 45. I can’t even imagine it now: reading a book for 45 minutes straight without reaching for my phone. But back then I believed in self-control. Drugs became tools to form an aesthetic, I had old professors pour their hot breath at me talking jealously about my future best sellers. (jinx) But I couldn’t do the schmooze. I was too busy practicing dribbling. All I wanted was to play a beautiful game. I jumped into the crowd for the foul and broke the fourth fifth wall. The key is not to think the key is just to do [insert improvisation to keep this a living piece of art]

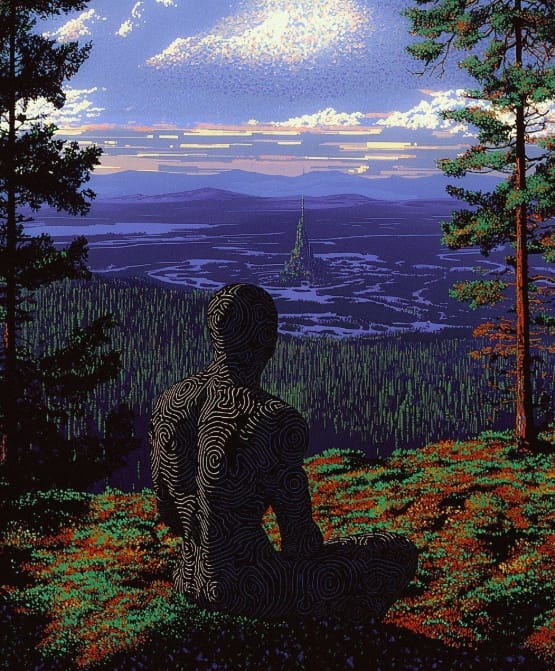

I open up VALIS, trying to do it in the same calm yet purposeful way that Odious used to do it in front of me. The book is still the same, but it’s my copy, which I sewed back together after pulling out all the pages and carrying them around in an extra large ziplock bag. I read the first words I see, the first ones my eyes happen to fall upon. I know the book so well it helps to keep my eyelids closed until the very last second, to lessen the deleterious effect of conscious choice. Even though I’m alone, the act of saying the words out loud reverses any curses. Outside, the sun lights up the glass bottles that The Babies have arranged on a spiral drawn into a patch of grey, lifeless soil. The bottles are filled with rain which they will drink along with the sunshine that is being soaked into it. I used to think it was the crazy outfits and giving up all your money but having a ton of rituals is what really makes up a cult. We eschew smudging with sage for words firmly stated; propositions, spoken into dark corners so the invisible helpers can hear. We take turns standing up and riffing. For this last round The Babies wrote down their thoughts and I quickly added them to my own and condensed it all into several sentences–connecting the words with colorful lines where appropriate. When it was done I sent it back with instructions for them to go to the always empty store and expand it many times the original dimensions (I’ve got my frequent consumer loyalty card) and print it out on the oversized printer. They smuggled it back to me and I spread it out in my room and painted over all the words with the same bone white paint leaving just the lines, each one blistered with pixels, which is revealed through the power of magnification as being its own secret language. The Babies hung it up on the garage door of Cyndi’s house as both a proclamation of endless war and infinite surrender and her oldest son sauntered over smoking a Winston in his sleeveless work shirt like the cowboy he should have been and said, “Is that supposed to be art? It’s just a bunch of stupid loopy lines. Anyone could do that.”

“Oh yeah?”, Cyndi hissed, her giant pointed tongue nearly smacking his pretty face, “so then why didn’t you?”

Image: Emilio Villalba

Thank you.

Love you all xo

There is a paid subscription option to get my posts PLUS the King of Spain Odious posts:

All $ goes to mutual aid projects like helping Tessa Dick keep her home. But I am happy to hook you up if $ is tight. Just let me know.

Or you can subscribe to just receive my posts (like this one) which will be sent to your inbox for free.

Peace IN,

--Swim